“What do you do?”

Baru and an ilykari priestess

“I try to save my home. Everything I do. For Taranoke.”

“You’ve come a long way to do it.”

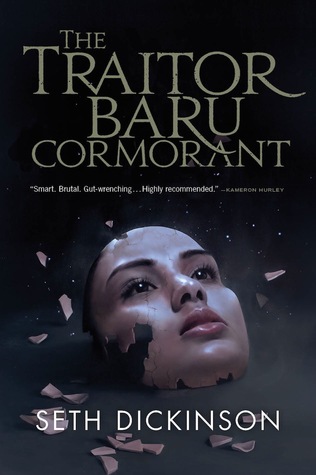

In The Traitor Baru Cormorant, Seth Dickinson crafts an unforgiving world filled with endless games of intrigue. Characters fight for power through weapons of economics, secrets, physical prowess, war, sexuality, and science. No sidelong glance is innocent, and no words can be taken at face value. The twists and turns of the plots within plots bring us on a journey complete with its moments of exhilaration, and moments of excruciatingly well-orchestrated devastation. It’s as if the author savours the act of twisting a blade in his readers’ hearts.

This is the truth. You will know because it hurts.

The opening lines to The Traitor. An early warning to be heeded.

At the heart of the book is the contest between colonisers and liberators. The Traitor opens with Baru’s childhood account of the colonisation of her homeland by the Masquerade. This subjugation doesn’t happen dramatically with guns and steel, but slowly, through the weapons of trade, education, and plague. And later, upon leaving her homeland Taranoke, we are shown a more matured progression of Masquerade Colonisation through Aurdwynn. From the start, and continuing throughout the book, we are presented with both the benefits of the scientifically advanced Masquerade’s rule (commerce, sanitation, education, etc), but also the accompanying costs (loss of autonomy, genocide, criminalisation of cultural norms and practices, etc). The internal conflict of these trade-offs plays out repeatedly in this book, clashing in a pattern that grows ever larger. We are invited to observe the Masquerade’s final test for Baru Cormorant, a savant selected and groomed by the Masquerade, to subjugate a foreign land. Along the way, we bear witness to her sometimes clever, sometimes miscalculated navigation and manipulation of these colonial tensions. She decides early on, that her best chance at overthrowing her colonial oppressors would be through treachery from a position of power. And throughout her endeavours, we are constantly reminded that she is but one of the many players on the board.

The exploration of these themes of colonisation are brought to life only because we see the conflicts raging through interesting characters. Without speaking too much about the roles and loyalties of each character, I’ll simply say that even with a cast full of dukes and duchesses with their followers and children, technocrats and their assistants, and not to mention characters that appear early in the book but are only mentioned in passing later; even with such a large cast, the reader is able to get a good sensing for each of them. Moreover, each character feels like an independent player on the board with their own missions and motivations. Instead of a story with clear protagonists and antagonists, everyone is both a potential ally and a potential antagonist. The stakes in this story are never low, the characters are well aware of it, and Seth Dickinson never lets us forget it.

After a good book, I usually wish I could forget everything that happened so that I may reread the story with the pleasure of first-times. After finishing The Traitor, I found myself filled with this same desire. But this time, I didn’t just want to reread the book for the first time, I wanted to return to a time when my heart didn’t ache so much. Because on a board with so many players, so many games of power and divided loyalties, victories and losses can only happen hand-in-hand. As an accountant, Baru herself must have known all along, even if she tricked herself into forgetting it, that the numbers ultimately have to be balanced.

Let it be clear though. My devastation is nothing but praise for the author Seth Dickinson, and for the traitor Baru Cormorant.